اولین تاس جهان ساخته ترکان اتروسک

The Turk Etruscan Dice

تاس ترکان اتروسک

اولین تاس جهان

Doç. Dr. Haluk BERKMEN

The origin of the Etruscan population is still unclear and is being

constantly investigated by scholars on cultural, linguistic and genetic

grounds. Several major authors of the Roman Empire, such as Livy,

Cicero and Horace called them as Tusci or Tursci (1). These names are in

good agreement with Tur-Osc, discussed in the previous chapter. There

are several indicators pointing to the Asiatic origin of the Etruscan

population. Their language is known to be non-Indo-European and many

similarities have been found with both the Altaic –especially with

Turkish- as well as the Uralic languages (2).

Recently a

serious genetic research has been published by a group of Italian

scientists. They have investigated several bone samples from the

Etruscan remains and came up with the following conclusions (3):

Etruscan sites appear to have rather homogeneous genetic

characteristics. Their mitochondrial haplotypes are very similar, but

rarely identical, to those commonly observed in contemporary Italy and

suggest that the links between the Etruscans and eastern Mediterranean

region were in part associated with genetic, and not only cultural,

exchanges. The Etruscans show closer relationships both to North

Africans and to Turks than any contemporary population. In particular,

the Turkish component in their gene pool appears three times as large as

in the other populations.

Since the Turkish population

originated –to a large extent- from Central Asia, it can be claimed that

the Etruscans too came to Italy from Asia, through the Alp Mountains in

the north of Italy. Their early settlements were on a high plateau

named Valcamonica, where they left many marks in the form of petroglyphs

(see Chapter 6 and 7). A further sign for their Uighur origin is the

name of the Alp Mountains. Alp means “tall and formidable” in Turkish.

There are several proper names starting with Alp; such as Alpaslan,

Alpagut, Alperen, Alper and Alp-Er-Tunga.

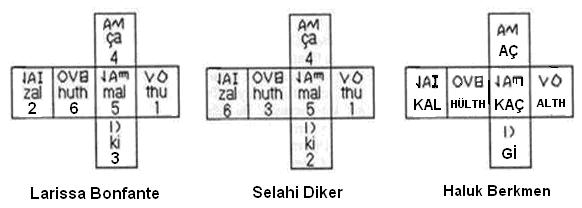

There are also some interesting Etruscan artifacts which have been the focus of interest and have created a lot of controversy among scholars (4). One of them is the Etruscan dice (left) found in Tuscany. There are no numbers on the dice but short inscriptions in Etruscan letters. Scholars have tried to decipher these inscriptions and came up with different names for the numbers from 1 to 6. J. Friedrich says (4).

The inscriptions on the dice -being without any doubt numbers from one

to six- gave rise to a large literature on this issue. But the order of

these numbers is still unclear.

Below we see three different

interpretations of the Etruscan dice. The one at the left is the

interpretation of L. Bonfante (5). The central one is the interpretation

of Selahi Diker (6) and the one on the right is my interpretation.

I

did not interpret the letters as words standing for numbers, but

instead words standing for actions to be performed. This is because

carving letters is much more tedious and difficult than carving numbers,

logically. One would not choose to carve the name of a number in place

of the number itself. The assumption that these words stand for numbers

is a modern preconception based on modern dices.

The first

observation which I made was to identify the word “Gi” written from

right to left. This monosyllabic word is the ancient form of “Giy”,

which means “dress up” in Turkish. The second two-letter word is read

from right to left as “Ça” by L. Bonfante and S. Diker. I read it from

left to right as “Aç” meaning “open” or “undress”. There are Etruscan

inscriptions which have been written in both directions. Such a system

of writing is called boustrophedon, meaning “as the ox ploughs”. In this

system the hand of the writer goes back and forth like an ox drawing a

plow across a field and turning at the end of each row to return in the

opposite direction.

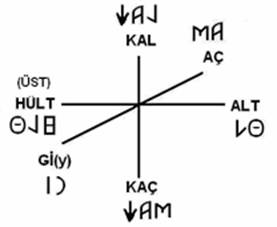

Once these commends have been deciphered

the remaining monosyllabic words could be easily identified as “Kal”,

Kaç”, “Hült” and “Alt”. These words are all words used still in modern

Turkish, with the exception of Hült. Kal means “stay”, Kaç means “run

away, escape” and Alt means “under, below”. Since we find opposite

meanings on opposite faces of the dice, it is obvious that Hült stands

for “over, above”, which is “Üst” in modern Turkish.

The H was probably aspirated and disappeared in modern Turkish. We can

see on the left how the six words are inscribed on the dice. Since these

words are certain commands to be performed, it is quite possible that

they had to be performed during a wrestling contest. My guess is that at

the start or during the contest the dice was cast by one wrestler and

he had to perform the command appearing at the top side of the dice.

These are: Kal: “stay erect”, Kaç: “run away”, Alt: “stay below”, Hült

“stay above”, Aç: “undress” and Gi: “dress”.

The Etruscan wrestlers could also wrestle totally undressed as the Etruscan wall painting below shows (7).

References

(1) Dictionnaire Illustré Latin Français, Félix Gaffiot, Librairie Hachette, 1934.

(2) Les Étrusques Étaient-ils des Turcs?, Adile Ayda, Paris, 1971.

(3) The Etruscans: A Population-Genetic Study, Am. Journal of Genetic Studies, March, 2004.

(4) Extinct Languages, Johannes Friedrich, Barnes & Noble, USA, 1993.

(5) Etruscan, Larissa Bonfante, University of California Press , 1990.

(6) The Whole Earth Was Of One Language, Selahi Diker, page 209, Izmir, 1996

(7) Ref. 1 of Chapter 4, Page 45.